Correspondence – Page 33

Correspondence

Page 33

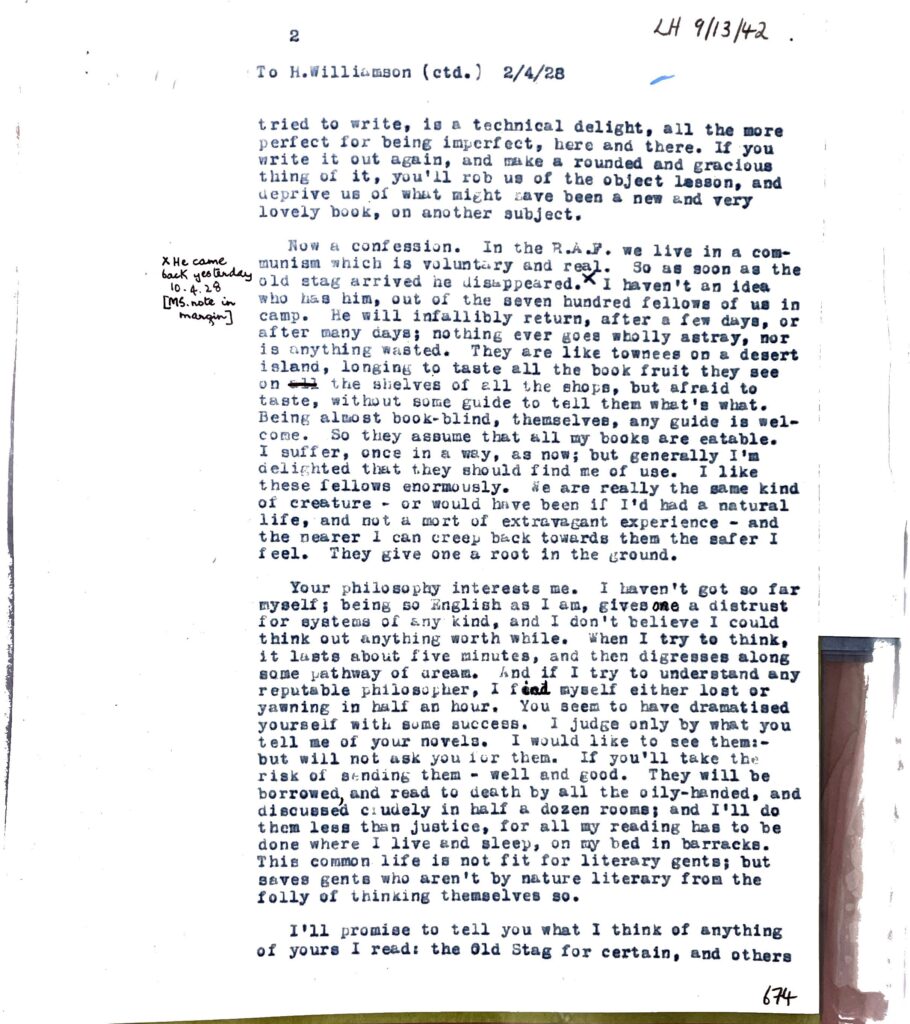

To H. Williamson (ctd.) 2/4/28

tried to write, is a technical delight, all the more

perfect, for being imperfect, here and there. If you

write it out again, and make a rounded and gracious

thing of it, you’ll rob us of the object lesson, and

deprive us of what might have been a new and very

lovely book, an another subject.

Now a confession. In the R.A.F. we live in a com-

munity: miniism “idth is voluntary and great. So as soon as the

old stag arrived he disappeared.[note to myself] I haven’t an idea

who has him, out of the seven hundred fellows of us in

camp. He will, inevitably return, after a few days, or

after many days; nothing ever goes wholly astray, nor

is anything wasted. They are like townsees on a desert

island, longing to taste all the book fruit they see

on ^ the shelves of all the shops, but afraid to

taste, without some guide to tell them what’s what.

Being almost book-blind, themselves, any guide is wel-

come. So they assume that all my books are edible.

I suffer, once in a way, as now; but generally I’m

delighted that they should find me of use. I like

these fellows enormously. We are really the same kind

of creature – or would have been if I’d had a natural

life, and not a sort of extravagant experience – and

the nearer I can creep back towards them the safer I

feel. They give one a root in the ground.

Your philosophy interests me. I haven’t got so far

myself; being so English as ’em, gives one a distrust

for systems of any kind, and I don’t believe I could

think out anything worth while. When I try to think,

it lasts about five minutes, and then digresses along

some pathway of dream. And if I try to understand any

reputable philosopher, I find myself either lost or

yawning in half an hour. You seem to have dramatised

yourself with some success. I judge only by what you

tell me of your novels. I would like to see them:-

but will not ask you for them. If you’ll take the

risk of sending them – well and good. They will be

borrowed, and read to death by all the oily-handed, and

discussed crudely in half a dozen rooms; and I’ll do

them just that justice, for all my reading has to be

done where I live and sleep, on my bed in barracks.

This common life is not fit for literary gens; but

seven gents who aren’t by nature literary from the

folly of thinking themselves so.

I’ll promise to tell you what I think of anything

of yours I read; the old Stag for certain, and others

Editor's Note: This text has been transcribed automatically and likely has errors. if you would like to contribute by submitting a corrected transcription.